Great Famine

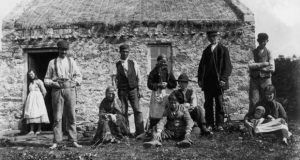

Causes of the Famine: Overpopulation and Poverty

In the early 19th century, Ireland’s tenant farmers as a class, especially in the west of Ireland, struggled both to provide for themselves and to supply the British market with cereal crops. The cause for this was the small size of their allotments and the various hardships that the land presented for farming in some regions. The potato, was appealing in that it was a hardy, nutritious, and calorie-dense crop and relatively easy to grow in the Irish soil and soon became a staple crop in Ireland by the 18th century.

By the early 1840s, almost half the Irish population—but primarily the rural poor—had come to depend almost exclusively on the potato for their diet. The rest of the population also consumed it in large quantities. This heavy reliance on just one or two high-yielding types of potato greatly reduced the genetic variety that ordinarily prevents the decimation of an entire crop by disease. This was a major reason of why the Irish became vulnerable to famine.

In 1845, a strain of Phytophthora (the cause of the blight) arrived accidentally from North America, and that same year Ireland had unusually cool moist weather, in which the blight thrived. Most of that year’s potato crop rotted in the fields and that crop failure was followed by more-devastating failures in 1846–49, as each year’s potato crop was almost completely ruined by the blight.

The Government’s Efforts to counter the famine

The British government’s efforts to relieve the famine were inadequate. Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peele did what he could to provide relief in 1845 and early 1846 and authorized the import of corn (maize) from the United States, which helped avert some starvation. The Liberal cabinet of Lord Jon Russell, which assumed power in June 1846, maintained Peel’s policy regarding grain exports from Ireland but otherwise took a laissez-faire approach to the plight of the Irish and shifted the emphasis of relief efforts to a reliance on Irish resources.

Much of the financial burden of providing for the starving Irish peasantry was thrown upon the Irish landowners themselves (through local poor relief) and British absentee landowners. Because the peasantry was unable to pay its rents, the landlords soon ran out of funds with which to support them, and the result was that hundreds of thousands of Irish tenant farmers and labourers were evicted during the years of the crisis.

On top of that, under the terms of the harsh 1834 British Poor Law, enacted in 1838 in Ireland, the “able-bodied” peasants were sent to workhouses rather than being given famine relief per se. British assistance was limited only to loans, helping to fund soup kitchens, and providing employment on road building and other public works. The imported cornmeal was not nutritious and led to nutritional deficiencies.

By August 1847, as many as three million people were receiving rations at soup kitchens.The British government spent about £8 million on relief, and some private relief funds were raised as well. The unfortunate part of the famine was that the impoverished Irish peasantry continued throughout the famine to export grain, meat, and other high-quality foods to Britain because they did not have the money to purchase the foods their farms produced.

As a direct consequence of the famine, Ireland’s population of almost 8.4 million in 1844 had fallen to 6.6 million by 1851. The number of agricultural labourers and smallholders in the western and southwestern counties underwent an especially drastic decline. The concentration of landownership was in fewer hands because of the reduction of small landowners after the famine. Thereafter, more land than before was used for grazing sheep and cattle, providing animal foods for export to Britain.

About one million people died from starvation or from typhus and other famine-related diseases. About 2 million Irish emigrated during the famine and Ireland’s population continued to decline in the following decades because of overseas emigration and lower birth rates. By the time Ireland achieved independence in 1921, its population was barely half of what it had been in the early 1840s.