Background

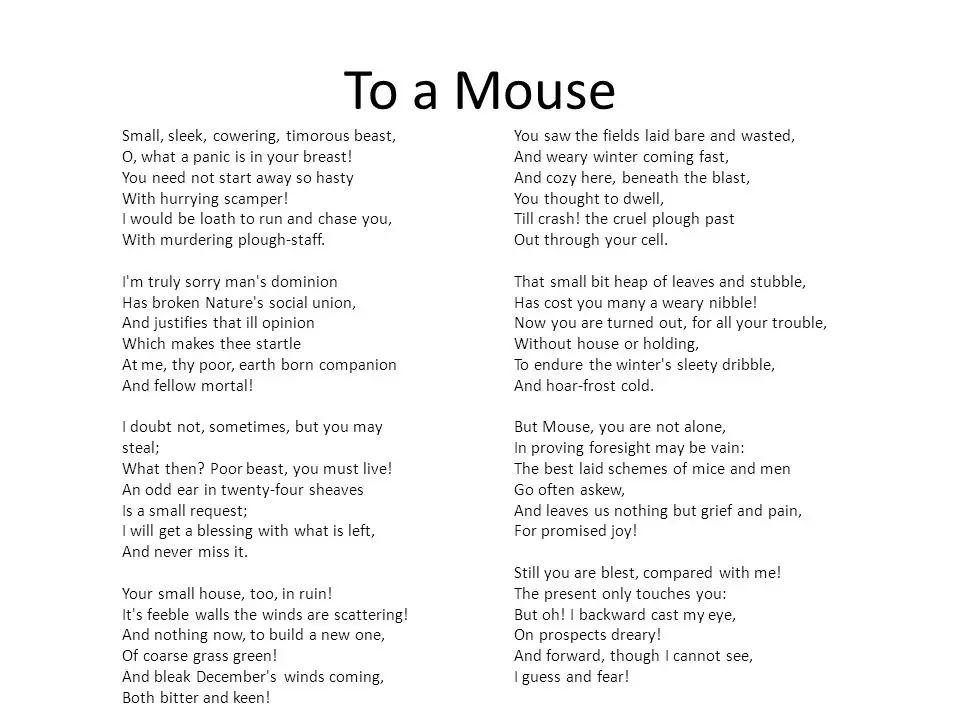

To a Mouse, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest with the Plough, November 1785 is a poem written by Robert Burns in the Scots language in 1785. Burns destroyed a mouse’s nest while field ploughing according to legend.

Summary

The speaker of the poem declares that he is aware of the characteristics of the mouse at the outset. It is little in form and is afraid of the presence of the living human species. The speaker empathizes and realizes why it was the case.

He continues by describing how the mouse’s well-constructed home was damaged by the winds, leaving it without a place to spend the winter.

In the last few words, he compares the mouse’s situation to that of the entire human race. No matter how carefully one gets to plan for the future, subjection to change remains inevitable.

Meaning

Burn’s regret about using his plough to destroy a baby field mouse’s nest is portrayed in the poem To a Mouse. He apologizes to the mouse for his misfortune and the general tyranny of a man in nature.

Form & Structure

Robert Burns’ poem “To a Mouse” has eight stanzas that are divided into sestets, or groups of six lines. The poem adheres to a consistent rhyme scheme that highlighted the humorous aspect of the narrative. The stanzas tend to use multi-syllable words and have an AAABAB rhyme scheme. The rhyme scheme is considered feminine and is reminiscent of children’s songs.

There are four iambs in each line because “To a Mouse” is entirely made up of iambs, which are groups of two syllables in an iambic tetrameter pattern. The pattern alters at the conclusion of each line. There is one remaining unstressed dangling syllable, called a catalexis.

Literary Devices

Robert Burns also employed a few literary techniques and strategies that are noted down below:

Imagery

Imagery is used to experience things by engaging the five senses. “Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste, An’ weary winter comin fast, An’ cozie here, beneath the blast, Thou thought to dwell- Till crash! , the cruel coulter past, out thro’ thy cell”.

Assonance

when vowel sounds are repeated inside the same line, it is called assonance. For example, the sound of /a/ in “Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste” and the sound of /ee/ in “That wee bit heap o’ leaves and stibble” are examples.

Consonance

Consonance is the repeating of consonant sounds inside a single line, like the consonant sound of /n/ in “I’m truly sorry Man’s Dominion”.

Alliteration

Alliteration is the rapid succession of repeated consonant sounds inside the same line, such as the sound of /c/ in “Till crash! the cruel of coulter past” and another sound of /w/ in “An” weary Winter comin fast”.

Symbolism

Symbolism is preferred to be used while representing concepts and characteristics that give deeper and more symbolic meaning to a narrative than their literal interpretations. For instance, “bleak December’s winds” is a metaphor for devastation.

Metaphor

This figure of speech implies a comparison between two things that are fundamentally unrelated. The speaker’s life is metaphorically depicted in the poem. He compared his ups and downs to those of a mouse.

Personification

Personification is the process of endowing inanimate objects with human characteristics. For instance, the poem uses a mouse to personify the fear of mice.

Enjambment

It is described as a verse concept that carries on to the following the line rather than ending at the line break

“I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!”

Analysis

Stanza 1

“Wee, sleeket, cowran, tim’rous beastie,

O, what a panic’s in thy breastie!

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi’ bickerin brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!”

The speaker introduces the mouse that is the subject of the poem in the first verse of “To a Mouse”. The speaker’s adjectives, which refer to the mouse’s physical and emotional makeup, are extremely illustrative and nuanced. It’s “Wee”, which means little, “sleeket” which means “sneaky”, “cowran” and “timorous”.

The mouse is described in the final sentences as being terrified and wanting to run and “panic” anytime someone approaches. The poem’s anthropomorphism is established by the speaker’s use of direct speech to the mouse.

The speaker appears to understand the mouse as she converses with him. These behaviours show that the speaker views the mouse as being comparable to or even equal to a person in terms of how he should treat her.

Stanza 2

“I’m truly sorry Man’s dominion

Has broken Nature’s social union,

An’ justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal! “

The poet begins to apologize to the mouse for the nature of people in the second stanza. They have “dominated” the earth and refused to accept beings that are different from themselves. On this list, the mouse, unfortunately, occupies a significant position. The desire of “Man” to rule over everything on the earth has “broken Nature’s social connection”. Animals are compelled to behave in ways they normally wouldn’t because of humans, who can cause sabotage their natural order. Humans hardly have the capacity to realize the value of small earthly species and habitats. They rarely take them into consideration and consequently, it is justified for the mouse to think poorly of the human race.

Stanza 3

“I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve;

What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

A daimen-icker in a thrave

’S a sma’ request:

I’ll get a blessin wi’ the lave,

An’ never miss ’t!”

The speaker discusses the mouse’s lifestyle in the third verse of “To a Mouse”. In the opening words, he tells the mouse that he is aware that “Thou mayst thieve”. The speaker is not bothered by the mouse’s need to steal food from people.

The fact that it has been reduced to this state is not the mouse’s fault. The mouse is similar to a “poor beastie” that “maun” or “must” survive.

An “ear of corn”, or “daimen-icker is a food that the mouse steals. When a “daimen-icker” has been sold from a “thrave” or bundle of twenty-four then it becomes merely small or little in form. Through the food the mouse steals, he will bestow his blessing upon it.

Stanza 4

Thy wee-bit housie, too, in ruin!

It’s silly wa’s the win’s are strewin!

An’ naething, now, to big a new ane,

O’ foggage green!

An’ bleak December’s winds ensuin,

Baith snell an’ keen!

The speaker switches to talking about the “housie” where the mouse resides at the halfway mark of this piece. It is “in ruin!” because holds no strong and grand structure, so the walls have become fragile and the wind frequently “strewin” them.

These sentences make Burns’ decision to highlight the Scottish dialect quite clear, especially in words like “wins and “wa’s” that aren’t typically contracted.

The mouse’s nest, or “housie”, has no supplies to build new walls even though the wind has destroyed the old ones. The time of year is not ideal to locate the necessary “green”. Unfortunately, as the “winds [are] ensuing” thereby December will arrive shortly.

Since it is now been December and the winds are icy and biting to the skin. So there is no time left, and on the other hand, the poet is excruciatingly feeling sad about the small mouse’s winter home being destroyed by avarice.

Stanza 5

Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste,

An’ weary Winter comin fast,

An’ cozie here, beneath the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

Till crash! the cruel coulter past

Out thro’ thy cell.

Finally, the speaker focuses on the mouse’s current circumstances. He is aware that the mouse made an effort to seek refuge in a “field” where it could be “cozie…beneath the blast”. It was here that it “thought to dwell”, but crashed instead.

The house erected was demolished by the wind when it passed through. The reader should note that this passage has an alliteration. The poet repeatedly uses the letter “C” to highlight the destruction caused by the wind and its “cruel” character.

However, he also stated that the heinous plough demolished the cell by passing through it. The shelter was destroyed and all the efforts were unsuccessful.

Stanza 6

That wee-bit heap o’ leaves an’ stibble

Has cost thee monie a weary nibble!

Now thou’s turn’d out, for a’ thy trouble,

But house or hald,

To thole the winter’s sleety dribble,

An’ cranreuch could!

The sixth stanza of “To a Mouse” was expanded with the description of the mouse’s former home. Although it is currently in ruins, the speaker still wishes to describe what the mouse created. Only a “wee-bit heap o’leaves an’ stibble”, or pieces of hay and grass were there.

Despite using little materials, it was expensive for the mouse. The wind “turned” the tiny creature out of its nest by negating all of the efforts. Now it has to contend with the “cranreuch” or “frost” and “winters sweetly dribble”.

Stanza 7

But Mousie, thou art no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

The speaker desires the mouse to dawn with the realization that it is not alone. Plans frequently fail, making “foresight” useless or futile because one can never predict what will happen. After this poem was published, the following lines gained considerable notoriety, particularly when they were used in John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice and Men.

The speaker deliberately states in the line “The best-laid schemes of Mice an’ Men/Gang aft agley”. The speaker wants to express the futility of foretelling the future because no one is enough capable of prophesying the

future in an exact way.

The speaker is addressing the entire human race as well as non-human animals and other living creatures. This is referred to as “you.” Everybody knows such plans will fail.

Stanza 8

Still, thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward tho’ I canna see,

I guess an’ fear!

In the final stanza of “To a mouse” the speaker portrays that the mouse is “blest, compar’d wi” him. The mouse only feels pain from the “now”, though. The little “beastie” does not have to be concerned either about the future or the past.

On the flip side, the “speaker is deft to “backward cast” his “e’e”, considering his possibilities in light of what has already occurred to him, they seem “dear”. Then, when he gazes forward into the future, he “canna see” or cannot see, the “fears” which may come for him, which can be a gloomy and menacing possibility.

Themes

Union: Human with Nature

The speaker of “To a Mouse” refers to a situation where human beings and animals are on an equal page and they are being considered as “earth-born companion’s/ an’ fellow-mortal[s]” He thinks that because they are fellow creatures, they experience the same struggles as human beings.

The mouse and the farmer both have to put in a lot of effort to get food and build a home for them. The same regular weather fluctuations, such as the severity of winter, affect both as well equally. Either of them risks having their diligent effort undone at any time. By mistake or spite, plans are derailed, leaving only grief and suffering for both mice and men intact.

Fate and Futility

The “best laid plans” can be derailed despite diligence and planning just as quickly and unexpectedly as the mouse’s nest was destroyed by the plough. The meticulously constructed nest is “cozie…/Till crash!” and it “has cost [the mouse] monie a weary nibble”.

Since it was demolished, the industrious mouse is now left outside in “winter’s sleety dribble”. The speaker bemoans the pointlessness of laborious labour. Often foreboding becomes futile since things “gang aft agley”. The plans that “promised joy” could just easily turn out to be a bummer.

The speaker acknowledges that he is more anxious than the mouse as he mulls over the inevitableness of an uncertain future. The speaker thinks about regrets from the past and the future while the mouse concentrates on the here and now.

The fate of the mouse and Burns’ own family are similar enough that readers who are familiar with Burn’s biography cannot help but draw those connections. The fruitlessness of hard labour is reminiscent of Burns’ father who was a farmer and spent his life farming which resulted in his passing and financial ruin.

No matter how hard they tried, neither the poet himself nor Burns’ father could make farming lucrative. Burns even succeeded in purchasing land with the money he made from his writing, yet he was still forced to give up farming. He had to start collecting taxes in addition to writing to make a living.

Concern for Vulnerable

The poem’s farmer narrator has an unprecedented amount of affection and sympathy for the mouse. Mice are typically viewed by farmers as pests that need to be eliminated. Instead, the speaker refers to the mouse as “fellow-mortal” and humanizes it by giving it traits like fear and planning.

He realizes that the mouse must have been scared at finding itself to be homeless overnight. The poem’s opening apology to the mouse emphasizes the sadness that the farmer’s social position results in dominion over weaker animals like the mouse. The speaker believes that he has broken their “social union” leading the mouse to dread him.

The mouse is having the desire to survive just like the underprivileged. The speaker acknowledges the mouse needs to steal the corn to survive. The speaker’s empathy and care for the mouse are indicative of a wider shift in society’s views on animals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Middle-class intellectuals were concerned about the nascent animal rights movement, and many of them made up Burns’ audience. However, the majority of people at the time continued to view entertainment and agriculture practices that today would be viewed as cruel and commonplace.

In 1800, one of the earliest legal initiatives to prevent animal cruelty was launched. Sir William Pulteney who was a Scottish lawmaker sponsored a measure to outlaw bull-baiting.

His bill on outlaws got rejected as legislation by just two votes and The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was incorporated in 1824. On a smaller scale, similar ideas have already been expressed in poems, pamphlets, and sermons.

Animals that were originally, almost solely valued as labour and food were increasingly kept as pets as society became more urbanized, and hunting only for the intention of sport came to be seen as barbaric. The Romantics praised nature’s oneness while philosophy and science shed light on the similarities between animals and humans.

These ideas shifted society’s sentiments ever-more in favour of animal rights. Burns shows compassion for “Mousie” in the poem. He can make societal remarks without coming out as hostile concentrating on a sweet and helpless animal.

FAQs

What is the meaning of ‘To a Mouse’?

Robert Burns’ poem “To a Mouse” portrays the unhappy condition of a mouse whose home was devastated by the winter winds. The speaker of the poem declares that he is aware of the characteristics of the mouse at the outset. It is little and frightened of people. The speaker emphasizes and recognizes the reasons why this can be the case.

What is the plot of ‘To a Mouse’?

Burns’ regret about using his plough to destroy a baby field mouse’s nest is portrayed in the poem “To a Mouse”. He apologizes to the mouse for his misfortune and the general tyranny of man in nature. He also thinks somberly about how fate plays a part in everyone’s life including his own.

What is a famous phrase from Burns’s poem ‘To a Mouse’?

The famous phrase from Burns’s poem To a Mouse is “The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry”.

What does the mouse symbolize in ‘To a Mouse’?

The mouse eventually comes to represent all the people who experience homelessness and misfortune in general in an unpredictably changing world.

What is the moral of ‘To a Mouse’?

The ineffectiveness of making plans for a bright future lack the face of unexpected events is the central theme of Robert Burn’s poem To a Mouse.

What is the language of ‘To a Mouse’?

Robert Burns composed a poem in the Scots language titled “To a Mouse, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest with the Plough, November 1785” in this language. It appeared in the Kilmarnock book as well as the poet’s other publications, including the poems in Scottish Dialect.

What is the main metaphor for a Mouse by Robert Burns?

The speaker’s life is metaphorically depicted in the poem. He compared his ups and downs to those of a mouse.

Who feels more pain the farmer or the mouse?

Here the farmer feels more pain than the mouse because he suffers from more agony as a result of his awareness of past wrongs and his level of knowledge has allowed him to be more cautious about the future.

For what reason does the speaker apologize to the Mouse?

As a spokesman of all humanity, the speaker proceeds to apologize to the mouse. He claims that because humanity disrupted nature’s social unity, the mouse’s negative perception of people in general and of the speaker, in particular, is truly justified.

Who wrote the poem ‘To a Mouse’?

The poem “To a Mouse” is written by the poet Robert Burns who is also known as “Rabbie Burns”. He is revered all over the world and is considered to be a lyricist and Scotland’s national poet.